Without the Gift: Being-unto-Death

The condition of sin doesn’t always show up as some dramatic rebellion.

Most days, it just feels like this:

worthless, ugly, shameful, and utterly hopeless.

And that feeling — not the theology, not the doctrine, but the raw sensation of it — is often the most real experience of life.

A kind of ache that hovers beneath everything.

I don’t feel those things constantly anymore — not in the sharp way I used to.

But I still recognize the pattern:

The aching nostalgia for something I can’t name.

The anxiety about a future I can’t control.

The pressure to “be present,” to “be grateful,” to “be better.”

And the deep, soul-weariness of trying to be — instead of simply being.

It’s like I’m trapped in a maze with no exit —

every path looping back into itself,

every doorway promising freedom but leading to another dead end.

…Then I reread Romans.

Paul, in classic Paul fashion, moves quickly to the solution — to the hope, the grace, the rescue.

Don’t we all love that?

But just before that, I stumbled on something that really resonated — something raw, honest, and oddly comforting:

“We’ve compiled this long and sorry record as sinners (both us and them) and proved that we are utterly incapable of living the glorious lives God wills for us…”

— Romans 3:22–23 (MSG)

And that was the moment it landed:

This ache isn’t just mine.

I’m not broken in some uniquely defective way.

I’m just finally feeling what everyone else is carrying — even if no one’s saying it out loud.

And then I stumbled across Heidegger’s phrase:

Being-unto-death.

And something clicked.

That’s what I’ve been living.

That’s what we’re all living.

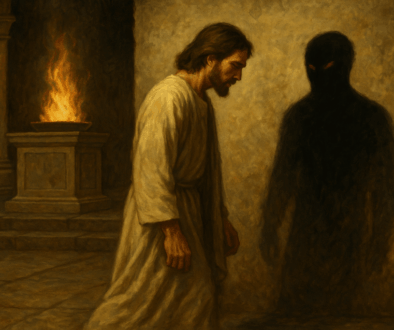

A Note on “Being-unto-Death”

In Martin Heidegger’s philosophy, Being-unto-death is not a morbid obsession, but a condition of self-awareness. It means living with the inescapable fact that death is the horizon of our existence — not in theory, but as something that defines our every possibility.

Most people flee from this awareness through distraction, social conformity, or constant motion. But to live authentically, Heidegger says, is to face death — to let it clarify what matters, and expose all the ways we try to escape finitude.

Here, I’m using his phrase to describe not only existential finitude, but the broader experience of being cut off — not just from God, but from wholeness, from truth, from the self we were meant to become.

And when I look at it through other lenses — theology, psychology, culture, even Buddhism — I see the same pattern everywhere.

This isn’t just a personal ache.

It’s the human condition, writ large.

The Ache We Carry but Don’t Name

We don’t speak about it much. Not honestly.

We talk about stress, burnout, overwhelm.

We share motivational quotes about “living in the moment.”

We talk about therapy, or mindset, or manifestation.

But beneath all of it is a deeper, more ancient truth:

We are not okay.

Not just because life is hard — but because we are estranged.

Estranged from God.

Estranged from the world.

Estranged from ourselves.

Paul calls this condition being “dead in trespasses and sins” —

“following the course of this world… carrying out the desires of the body and the mind, and [being] by nature children of wrath” (Ephesians 2:1–3).

It’s not just that we do wrong things — it’s that we’ve become entangled in a way of being that is against life.

Tillich put it like this:

“Sin is separation. To be in the state of sin is to be in the state of separation.”

And in that state, we try to build a life.

We perform. We hustle. We curate.

We adopt ideologies to explain the ache.

We cling to habits and addictions to soothe it.

We use religion to control it.

We use relationships to escape it.

All of it becomes a kind of spiritual play-acting —

an attempt to live without ever truly facing the truth.

The Unsatisfactoriness of Everything

Buddhism names this ache with startling precision: dukkha.

Not just suffering — but the basic, baked-in unsatisfactoriness of life lived out of alignment.

In the Dhammapada, the Buddha says:

“I wandered through many births in samsara, seeking the builder of this house. Painful is repeated birth.” (v. 153)

In Buddhist thought, samsara is the endless cycle of death and rebirth — a cycle not celebrated, but escaped. It’s not reincarnation as reward, but repetition as suffering. Even if life could continue endlessly, the Buddha says, it would still ache.

Still fall short. Still not be home.

And while many in the West — especially Christians — may not share a belief in reincarnation, we can still recognize the existential weight of that cry.

“Painful is repeated birth.”

Isn’t that what many of us feel?

The ache of repeating the same patterns.

Of waking up to the same emptiness.

Of trying again and again to build a life that holds… and failing.

Even joy is tinged with the ache of its passing.

Even love makes us afraid to lose.

Even peace makes us anxious — because we know it won’t last.

We crave wholeness, but we chase it in fragments.

We chase pleasure, escape, transcendence — but we never arrive.

We live not with death in mind, but away from it.

We deny it.

We build towers of meaning on sand.

And when those towers wobble, we panic — or distract — or pretend.

Paul writes,

“The wages of sin is death.” (Romans 6:23)

Not just eventual death — but a living death.

Sin doesn’t just break the rules. It breaks us. It dis-integrates us from our Source, our purpose, our joy.

As Nietzsche put it:

“When you gaze long into an abyss, the abyss also gazes into you.”

(Beyond Good and Evil, §146)

The Self We Perform and the Self We Bury

Many thinkers have described the ache of being two selves at once — the one we show, and the one we bury.

Thomas Merton called the first the false self —

“The self that wants only to exist outside the reach of God’s will and love… the self that exists only in response to social compulsions.” (New Seeds of Contemplation)

Søren Kierkegaard warned:

“The greatest hazard of all — losing one’s self — can occur very quietly in the world, as if it were nothing at all.” (The Sickness Unto Death)

Marion Woodman, circling closer to the body and psyche, wrote:

“The unlived life does not just disappear. It waits for us in the basement.” (Addiction to Perfection)

Carl Jung named this buried part the shadow —

“The thing a person has no wish to be.” (Psychological Aspects of the Persona)

But we don’t escape it by denying it.

We become haunted by it — projecting it onto others, or performing a false wholeness we can’t sustain.

We become, in time, exhausted actors on a stage we didn’t choose.

And the tragedy?

The soul knows the difference.

And We All Know It

We see it in the scrolling.

We see it in the rage.

We see it in the addictions.

We see it in the quiet disconnection of everyday life —

the way people smile but don’t look you in the eye.

Paul names it plainly:

“Claiming to be wise, they became fools, and exchanged the glory of the immortal God for images…”

— Romans 1:22–23

We are beings walking toward death —

not just biologically, but spiritually.

These images — the ones we curate, consume, compare —

they don’t just distract us from the ache.

They distract us from the divine.

They cover the ache, but they also bury the invitation.

We’re not just dying.

We’re living as if death is our core identity.

As if alienation is normal.

As if numbness is peace.

We don’t speak it,

but we feel it —

in our silence, in our habits, in our bones:

This isn’t how it’s meant to be.

No False Hope Here

I’m not ending this with a resolution.

This post isn’t about hope. Not yet.

It’s about seeing.

Heidegger insisted that being-unto-death is not a problem to solve, but a condition to face — something to lean into, not run from.

We must acknowledge it, own it, take responsibility for it.

To flee from death is to flee from the truth of who we are.

But to turn and face it — soberly, clearly — is to become free.

“Only the authentic being-toward-death unveils the possibility of being one’s ownmost self.”

— Being and Time, §53

And yet, it’s not enough to simply name the ache.

We must feel it.

We must let it in — not as a concept, but as a visceral truth.

The despair, the hopelessness, the weight of futility — they must be allowed to speak.

And to avoid that?

We create images.

We construct personalities, platforms, distractions.

Not just to distract from the ache — but to avoid the divine.

To not feel the ache, we build false selves.

And the tragedy is, we start believing they’re real.

Because until we stop performing — even to ourselves —

and let the ache burn,

it won’t transform us.

It will just keep hiding under everything we do.

Paradoxically, it’s only when we see the cold, hard truth that it stops owning us.

“For when I am weak, then I am strong.” — 2 Corinthians 12:10

Naming is the beginning.

But experiencing it unflinchingly — letting the sorrow and hollowness run their course —

that’s where true strength begins.

And Paul, for all his soaring words of grace, never skips this part:

“All have sinned and fall short of the glory of God.” — Romans 3:23

“I do not understand what I do. For what I want to do I do not do, but what I hate I do.” — Romans 7:15

Before grace heals, the ache must be seen.

Before life begins, death must be faced.

So this is me saying it out loud:

We are lost.

We are hollowed out.

We are curved inward on ourselves,

and yet forever aching outward.

We are, all of us,

being-unto-death.